“I can suck melancholy out of a song, as a weasel sucks eggs”. Thus Jacques, a grumbling lord in As You Like It who has taken to wandering the woods in solitude, begs his companion to sing more of the dirge he has just heard, so he can continue to glut on his own melancholy. The man’s obstinate, brooding self-absorption is a matter of widespread hilarity among the interim society in the Forest of Arden. He is much sought after by members of the Duke’s entourage, only to be ridiculed for his pigheaded lugubriousness which has become a comic liability. The comedy ends, as always, with marriage, but before the revels are concluded, Jacques solemnly excuses himself from the party, because the mood doesn’t chime with his beloved melancholy. “I am for other than for dancing measures,” he declares.

Paris, March 1995 – Von Trier writes the Vow of Chastity with Vinterberg over a glass of wine. “The movie has been cosmeticized to death” Von Trier bleats in a feverishly written manifesto called Dogme ’95, the name a provocative echo of the 95 Theses Luther had nailed to a church in Wittenberg five hundred years earlier.

Both zealous and ironic, it was a confrontation forged of that same belligerent puritanical spirit, by now ingrained in the more stringent aspects of the Northern European psyche. More than anything, in the Danes’ wishful smashing of the cinema’s false idols, was the sense that the film-makers needed this antagonism to propel themselves. Even though the premises of the manifesto didn’t quite cohere, they sounded good. Like something you could really believe in. Throw yourself into.

Dogme ‘95 was a gesture as antagonistic and Puritan as it was a sentimental throwback to other ‘movements’ of the sixties, which were no less self-conscious, but perhaps more organic, in that they seemed to be influenced by no other movement but their own – Nouvelle Vague and Neo-realism being the obvious points of reference.

The Danes were frustrated by the sudden decline of the counter-culture. They were looking for their own New Wave, and the nineties’ exponential improvements in technology provided a raw material for that counterpoint – a new means of production which empowered the amateur, much like the printing press had done for medieval preachers who suddenly found that they were able to circulate the teachings of scripture unmediated by hierarchical decree.

Spoiler alert: the technology survived; Dogme didn’t. Nonetheless, for the industry it was the first (and only?) formal colonization of the digital camera as an emblem of spiritual superiority – as inhospitable to the viewer as the icy terrain that had born the Danes – and that was how they wanted it. A truth-seeking, a struggle to feel, to comprehend, set against those false idols of the mainstream that offered nothing but an entertaining reassurance.

Hollywood had also become synonymous with a ballooning of cash. Dogme may have been challenging, but it was the viable, economically sustainable model – its ethos that of the commune. Luther’s contempt for an endless pile of bishoprics and episcopates provided a vivid analogue for Von Trier’s less than sympathetic attitude towards the fat cats living it up in that decadent West Coast city. A coterie of suited bureaucrats (he imagined, having not set foot there), who had grown too used to lounging by the swimming pool, splurging on their films with a quality of sentiment that was as prodigal as if they were paying for the tummy tuck of a favoured mistress.

Cosmeticized. The squeamishness around this word had everything to do with the suffocation of nature it implied – a nature Dogme wanted to unleash, where Hollywood would train it. At least that was the theory.

When Lars Von Trier was banished from Cannes this year after his Nazi gaffe, you could sense the spite in the air. It was the ones who, 16 years after that troublesome stunt, had had enough of this man’s antics. The ones who were just plain tired of this pugnacious, arrogant Dane, constantly provoking them, releasing these relentless, incendiary films, barely disguising his contempt for the audience, endlessly talking shit to the press. All those who had been exasperated not only by his gall, but by the self-indulgence of his conceits, the unapologetic obfuscatory stubbornness of his persona. These were the ones who stoked the flames – the same ones that panned the new film as a brooding clunky mess which did one thing worse than offending its audience – it bored them.

Never mind that it was just a crap awkward joke – that he was not endorsing Hitler, but trying to understand him (how unthinkable!) – Von Trier’s time had come. It was now, as an official persona non grata, that he unwittingly played out the role he had always been so fascinated with in his films: the pariah – usually the strong female lead whose innocence is crushed by the unforgiving, thoughtless society she finds herself a part of. One can always feel how much of himself he puts into those roles – how much it takes out of him.

It is a story as old as Shakespeare, and much older. The scapegoat, the black sheep. What was interesting this time, was that sense of self-imposed retreat which imbued the film itself. “LARS VON TRIER MELANCHOLIA” the opening title reads, as if this were his melancholy – a transposition of his own alienated speculation. Kirsten Dunst, c’est moi. It was as if that air of prophecy, so ubiquitous and uncomfortable in the film itself, had spilled over into reality, and the embarrassment caused by the main character’s inability to behave properly at her own wedding, was now repeating itself at the Cannes press conference – that most tedious and inevitable of ceremonies – at which Von Trier was himself incapable of behaving. In all the pictures, looking at him nervously, confusedly, was Kirsten Dunst, the newest filmic incarnation of Von Trier’s own ego.

The reception which has greeted his last two films in some quarters is much like the amused skepticism directed towards Jacques in As You Like It. Perhaps it’s a defensive way of ensuring that his insights can’t touch you. His grand notions laughingly dismissed, his pretentions ridiculed. In Antichrist, I could only laugh. Because for me, it’s difficult to imagine anyone conceiving of a fox eating his own flesh and saying “chaos reigns”, without immediately breaking into laughter.

But Melancholia is a different kettle of fox flesh – the dyspeptic afterbirth of Antichrist. Where the last film aimed for a direct assault on the nervous system, Von Trier has sculpted his newest brood into an outlet for apocalyptic rumination which dreams of the last moments on earth as a prolonged hangover after a night of failed revelry.

Unlike Antichrist, there is nothing here that is overtly gruesome, and yet I saw Melancholia with a friend who had to walk out half way through, because she found it too disturbing. Even when it’s being boring, it is overpoweringly moody. That is what shocked me, when I was trying to figure out why I had not enjoyed it. “Nothing happened!” I thought to myself. And yet I realized, with growing awe, how he had managed to sustain that horrible mood throughout the whole thing. The whisper of dread that was always present, no matter how vapid or clumsy the dialogue.

Given the history of Dogme, it would be easy for us to see Melancholia’s raving millennialism as coming straight out of the 16th century. This wouldn’t exactly be wrong. Who could be confronted with such a surly contrarian as Von Trier and fail to be reminded of the ranting Puritans? It is an attitude at once unhinged and energetic, a furious stubbornness which after all the cant is done, always ends up being the only attitude which has enough momentum to disrupt the ingrained flatulence of received opinion.

But whilst Justine’s Lutheran fatalism contains the icy energies of Dunst’s own Nordic ancestry, the ideas in Melancholia come from quite a different source – a much later, but equally recalcitrant, German thinker – Friedrich Nietzsche. And above all, his early work The Birth of Tragedy.

The big pun of the film is that Claire, the efficient and sensible sister who has organized a wedding (the formalities of which Justine finds difficult to bear) and who takes good care of her depressed younger sibling, is actually the least equipped to deal with the stress of a colossal disaster. Justine, who cannot even muster the strength to step into the bath without being overcome by existential dread, is comparatively peaceful and resigned in the face of the coming apocalypse.

The dynamic between Claire (Gainsbourg), and Justine (Dunst) is a barely veiled transposition of Nietzsche’s dialectic between the Apollonian and the Dionysian, two opposed yet inter-related artistic dispositions. In an unequivocal mimicking of Nietzsche, Claire’s ordered, rational and self-disciplined behaviour, channels the Apollonian; whilst Justine, the hermit, seer, and intoxicated imp, is pure Dionysus.

While the characters play out this fraught but somehow necessary dynamic, both inter-dependent and antagonistic, the film carries that tension into its visual language: this is particularly the case with Von Trier’s use of both the luscious, camply staged cinematography (characteristic of his early films) and the looser, lighter camerawork recalling the vérité immediacy of Dogme.

Perhaps the biggest preoccupation of Melancholia is that Nietzschean one of scale: the difference between the trivial and the cataclysmic. After we have seen the vast, bold, pompous, sublime, grandiose glimmers of the apocalypse in the opening montage, the formalities of a wedding ceremony take on a perverse ridiculousness. The necessity of decorum, epitomized by the various intricacies of table manners, ceases to have meaning, even for the people who are persuaded to adhere to it.

Dunst as the catatonic sprite with a proclivity for solitary brooding fails to respect the dignity of a golf course by walking out for a nice mid-nuptial piss. Here, golf is a modern extension of the grand country garden, (that old 18th century idea of an Enlightened training of nature): an exemplar of the human capacity for symmetry and proportion, and the site where Von Trier exacts his vengeance on the human race. In this climate of spiritual dread, the golf course as an emblem of trivial activity takes on the aspect of an absurd misguided endeavour, like the stretched limo in an earlier scene which tries and fails to navigate its way through the rugged landscape. They are shapes which fit the human, like the fork and the knife, but have very little to do with the raw elemental forms of nature.

The same force that compels Claire to avoid these insights, and to paper over the depth of suffering that they entail, also enables her to function as an upstanding citizen, someone whose sphere of interest has adapted to the modern modes of survival. This is why, when it becomes clear her efforts are in vain, she collapses, unable to deal with the prospect of annihilation, the condition of nature that has always been there, but that humanity has ceaselessly tried to wriggle out of.

Melancholia has come fully under Nietzsche’s orbit of thought. It is as if that dangerous iconoclast is Melancholia itself, a beautiful and horrifying planet bearing down upon earthly notions, a collision course which will be the human’s ultimate dismantling.

*

The role of Justine was initially going to be played by Penelope Cruz, before she opted out early on in pre-production, so she could do Pirates of the Caribbean 4. Interesting to note, seeing as Cruz’s mentor, Pedro Almodóvar, also released a film at Cannes this year, which is so completely opposite to Melancholia, and yet beneath the stylistic differences, so peculiarly, so weirdly similar…

The ‘cosmetic’ was something squeamishly alluded to in Von Trier’s Vow of Chastity. But what of the parts of Europe that had been left uncorrected by the Puritanical fanaticism of the Reformation, the parts for which that Viking severity was a wholly alien spirit, something sullen and perverse? What of the world that shaped Almodóvar, whose films have long been wedded both figuratively and literally to the cosmetic, and nowhere more so than in his newest film, the story of an evil plastic surgeon?

The Skin I Live In is set in Toledo, which should immediately remind us of Tristana, Buñuel’s famous Toledo film, also about an aristocrat’s unsuccessful attempts to mould his heroin. Toledo, the place where Buñuel and Dalí used to holiday; Dalí, that other cosmetician, whose glossy paint depicted with such lingering detail the glazed and dripping skin which was the raw material of disturbing dreams, the currency of time. Perhaps much can be learned from Dalí’s polished controlled attempts to depict the nightmare of the subconscious – a realm where one yields all control and all gloss to some sort of primeval force, a force that is also purely ‘you’.

But it is the actor Fernando Rey’s model of the obsessive patriarch that Antonio Banderas most resembles as Dr. Ledgard, a kind of 2.0 version of Buñuel’s wooden and aristocratic sociopath, hiding his manias under the guise of distinction. We are led to believe that Ledgard’s failed attempts to control or understand the other women in his life – the wife who cheated on him and died; the daughter who was insane, who feared him and then died – are the reasons for him wanting to remake his daughter’s assailant in his wife’s image – an image which acts not as a person, but as an image – docile, obedient, manipulable.

Even though Don Lope in Tristana was supposedly a socialist, when you saw his subtle insidious ways of incarcerating Tristana, of keeping her trained, away from society, you couldn’t help but think of Franco and the tragedy of Spain’s subjection to Falangist rule. Just so, Don Lope 2.0, Banderas’s charming expressionless ogre, who talks emptily of progress and humanity, is a fascist; and the sequestration of Vincente/Vera away from society, entrapped in a locked room, is analogous to the isolation of Spain during the Franco years, forgotten to Europe for so long, left to live out a musky obedience to the General.

You would expect someone like Almodóvar, a gay, madrileño bohemian who grew up under Franco, and whose own artistic liberation was only made possible by the death of the dictator (and the dawning democracy that it signified), to fix onto this dynamic of oppressor and captive within the novel that forms the basis of the film (Thierry Jonquet’s Tarantula).

But what is really fascinating (and typical of Almodóvar) is how this struggle is figured along the lines of gender. This film is like the evil twin sister of All About My Mother: in the latter film, Almodóvar made us see that even those of us born with a penis can find the instincts of a mother somewhere within us.

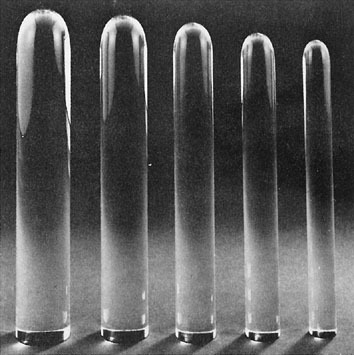

Here, the hostage, by having an unwanted vaginoplasty, is literally forced to find the woman inside of him. In one hilarious and disturbing scene, the newly evacuated Vincente is shown the different sizes of euphemistically named ‘dilators’ (dildos) which stand erect on a table in ascending order: we see Vincente struck dumb in a striking reverse angle which looks through the dilators, framing the shot as if they are his prison bars – the impositions of gender. The implication is clear: gender is a mould which you can either embrace or fight against, but it is not essentially ‘you’.

This ‘you’, which Vera seeks and, with the help of yoga and Louise Bourgeois, finds, is not Dali’s ‘you’, the frightening mutable subconscious: it is something irreducible and quiet, a noble place lodged deep inside where no-one else can get to it. Vera chooses to embrace this place inside – it’s all she has, and it’s the only way out of her predicament. Ledgard’s desire is narcissistic, and pure delusion – an inflated belief in his own lovability. Vera understands and exploits the skin she has been forced into – understands that it is not her own, but a reflection of her oppressor’s desire – a desire she tries to make more acute by increasing her docility (making him breakfast, wearing his work shirt) which with heavy irony, enhances her liberty and control.

The last scene is not only Spain’s dazed and fragile reconciliation with Mother Europe, but Almodóvar’s own coming out, not just sexually but as an artist. Indeed, every new film is a coming out. What will mother think? Will she recognize me beneath this new identity? And while Vera is ultimately liberated from the rigid grip of her oppressor, she still bears the marks of her suffering. As does Almodóvar, in the most complex and fascinating of ways.

This is because Almodóvar doesn’t just identify with the victim of the piece, but bizarrely, with the oppressor as well.

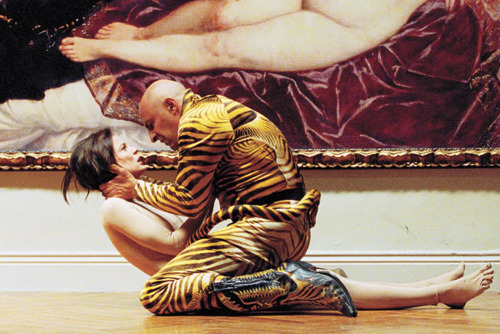

Whatever you say about Robert Ledgard, he’s a wonderful surgeon. Absolutely first class. After Broken Embraces, Almodóvar began to express his own love for cinema: “Life is imperfect, for everyone. Cinema makes it a little more perfect”. This is, after all, what Ledgard does for his patients – he endows them with the power to express themselves (so he says), and then warbles about how much he has been moved by his own administrations, the goal of which is the training of nature, making the human perfect like a golf course. We watch him being anal with his breakfast; folding wire round a bonsai. Fire is his black beast, nature’s elemental sign of passion and destruction, the thing he strives so industriously to make the skin resistant to. His antipodal brother is dressed as a Tiger – Blake’s burning emblem of immortal nature (“what art could twist the sinews of thy heart?”) – the force that must be kept at bay.

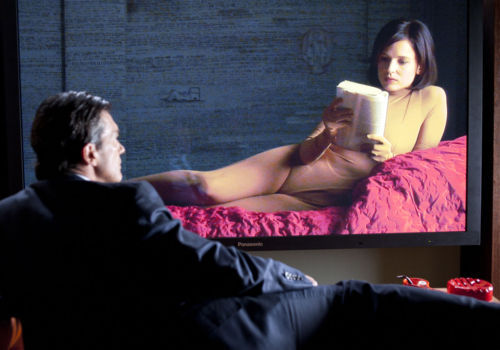

Despite his ultimate intentions, Ledgard’s clinical, obsessive appetite for perfection is something Almodóvar himself strives towards. The unerring precision of the filmmaking on display is quite blatantly echoed in this evil surgeon’s own meticulous procedures and operations. Here, the old pun of ‘final cut’ is an obvious and useful one, because the most vital thing the director has in common with his protagonist is absolute creative control. The scene where Ledgard looks with the scrutiny of an old master at Vera reclining on the big screen like the Venus d’Urbino (which hangs above the stairs), and impulsively zooms in to glean the image for imperfections, parodies the tense vigilance of an alert director in the editing stage of production. In this respect, the skin is the film, that paragon of pleasure, the forging of which the director-surgeon is tirelessly preoccupied by. Ledgard is told to stop his experiments because they are against the rules, and in this way his persistence lives out the macabre fantasy of Almodóvar, who has always had a mischievous tendency for taboo-breaking.

And yet who could deny that this character is a monster? That whilst there is this uncomfortable correlation between Almodóvar and Ledgard, ultimately Vera is the one that everyone sides with? She is where the director has placed his emotional investment.

At some point, one has to talk about Penelope. Stranded somewhere back in Ithaca whilst her beloved Pedro battles with the Cyclops. When a past collaborator returns to chastise Ledgard, having cottoned on to his devilry, Vera emerges from the shadows, confirming herself as a willing participant: “My name is not Vicente. It’s Vera. Vera Cruz!” This is a characteristic in-joke, but it makes us wonder where indeed Penelope is in all of this. It’s easy to see why Mrs. Bardem (née Cruz) isn’t here, because it’s not her type of role. Cruz is always so emphatically present in the scene that, while it’s conceivable she could have pulled off the stilted behind-the-eyes acting of absence or detachment that Elena Anaya does so convincingly, perhaps Almodóvar didn’t think this role would be playing to Penelope’s strengths. Nonetheless that little ‘Cruz’ joke leads us to wonder whether Ledgard gave Vicente that name too (as well as the name ‘Vera’, which means ‘faith’), or whether it was Vera herself who seized upon that spirited beacon of womanhood, and perhaps took inspiration from Cruz’s own portrayals of courageousness in suffering…

The release of Broken Embraces saw Almodóvar and Cruz give many interviews about their relationship. It’s not just close, they said, it’s a kind of symbiotic nourishment whereby he sees things in her which even she herself cannot see, and vice versa. A dynamic of absolute faith in each other – an exacting artist and his obedient muse, moulding each other in art. The relationship between Ledgard and his optimistically named muse (Vera: faith) is in many ways the hideously inverted transposition of that mutually fortifying artistic bond. “It is best for an actor to believe you’re not being watched” says Penelope, and we immediately think of how Vera is under constant supervision. This is the shape of that robust partnership between director and actor, watcher and watched, but evacuated of its conditions for health. In this inversion of the gifts of influence, it has degenerated into pure subjugation.

“Did you pray?” the mother hilariously, pathetically asks her son after he has butchered his brother. This, like all of Almodóvar’s jokes, is a symptom of something deeper, less flippant than it appears. It forces us to ask ourselves a question about the director himself: how do we reconcile this perverse delight in and simultaneous condemnation of his protagonist’s fixation with procedure? To answer this we must look to the perennial embodiment of Southern European delight in surfaces: Catholicism.

It has never been a very hard leap for dissident Spaniards to make the correlation between fascism and Catholicism, mainly because it was the Church that sided with the Falangists, more out of self-preservation than ideological approval. But they are in fact uniquely compatible, not only in their love of authority, order and ceremony, but in their lust of façade, their fetishes for powerful objects and veneers.

Ledgard’s fastidious observation of ritual is a completely natural fascination for a director who has imbibed the forms and energies of Catholicism, out of necessity rather than choice. Almodóvar’s parents sent him to a religious boarding school because they wanted him to become a priest: his experiences there form the basis of La Mala Educación, where we are shown how cinema not religion was his real education.

But then again, what does the cinema, specifically that of Hollywood, provide other than authority, order, ceremony, lust, veneer? That is it’s basic appeal!

Ledgard washes the forceps, the hemostat, and the speculum, as a priest might covetously fiddle with a chalice, a ciborium, or a monstrance; or indeed, as a cameraman might meddle with his lenses, filters, tripod, or his light meter. All interfaces between the body and the body’s projections: its spirit, its actions, imagination and perception.

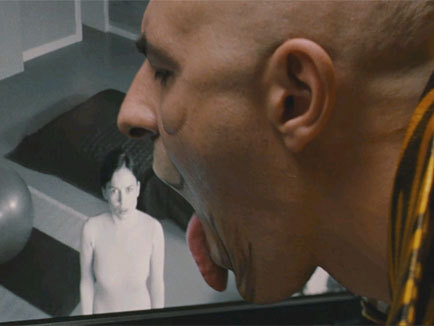

“Any further improvements?” Vera asks, like a naïve congregant plied for confirmation. Meanwhile, the clergyman moves his sacrificial blood between containers, the body concocted in a petri dish: the articles of transubstantiation – of divine life within the sacrament, an immortal skin which Roberto the Tiger, hungry for the Eucharist, rapaciously attempts to consume. The same Tiger who sees the divine being on a small, black and white screen, as if it is a gateway to another world, a Purgatory.

If cinema is divinity, perhaps genre is denomination – the ultimate skin one lives in for an hour and thirty minutes. Who are Almodóvar’s saints? Whilst Von Trier’s heroes are masters of the sublime as expressed in a kind of slow and stoical grandeur (Dreyer, Tarkovsky, Kubrick), Almodóvar is all exuberance. Undoubtedly his films have been touched by the opulence of mid-late Fellini (another lapsed Catholic), but at their core, really they are stacked to the hilt with a nostalgic infatuation for Golden Age Hollywood. The luscious, camp musicals of Minelli, in their dazzling saturations and striking design sharply executed; the gaudy and thrilling histrionics of Ray and Kazan; the sentimental melodramas of Sirk; or even Wilder’s droll sensationalistic jaunts. Above all, in this film, Hitchcock. In the complex dynamics of looking; and the shaping or projecting which happens with that looking, his touch is everywhere.

Perhaps ultimately Almodóvar is telling us that these stylistic benchmarks, these obsessions, are what he understands himself by, at least in a formal sense. But surely he is also saying that, after we have been thrilled by such technical orchestration or artistic virtuosity, the most important thing is what’s inside the box; our ability to see through the seductive image into the depth contained, to apprehend what is found there with humanity and with humour and compassion – those indispensable, fragile qualities which Ledgard, Catholicism and the Falange, are all deficient in.

*

These two films are so wildly different, and yet what do we make of the fact that they are both set in the secluded mansions of rich men? That both films are deeply concerned with the kinds of retreat, both physical and psychological, enacted by their characters? That both films are entangled with ideas of depth and surface?

Moreover, both films contain an echo of the stylistic shifts that each director had adopted in their previous films. For Almodóvar, the tight grip of genre, particularly film noir, in Broken Embraces, was not exactly unprecedented, but it was an acute sharpening of any former tendencies in that direction – a new tightness which has clearly been repeated in The Skin I Live In. With Broken Embraces, Almodóvar was suddenly more eager to adhere to generic conventions than he had been in previous films, which had always self-consciously flirted with the sensational effects of genre, but never plunged quite so whole-heartedly into it as now.

Meanwhile Von Trier’s Antichrist introduced another level of ferocity and gruelling affect, married with a new, grimly varnished aesthetic, in sharp contrast to everything he had made from the nineties onward. The films had been consistently gruelling, but their staging was being progressively stripped down in a way which, after the sublime ‘Golden Heart’ films, was starting to become stodgy. Melancholia is another step away from the nakedness of Dogme, to a kind of po-faced, macabre baroque, which had already been gestating in Antichrist.

That these stylistic adjustments occurred in both directors simultaneously, at such a point in European history, is suggestive to say the least.Europe’s two hot-shot auteurs have been imbibing some sort of energy. These films come on the cusp of worldwide financial meltdown. Could it be that two uncompromising artists, whose respective careers were nurtured by the boom years and now enter into the dark age with us, are absorbing the apocalyptic decline of European society?

Europe shudders – every nation is suffering, but now more than ever that age-old split between the austere and the profligate rises to the surface. Northern Europe helps its depressed sister into the bath – she refuses to get in. Southern Europe is punished for its days of wanton abandon, held captive by an austere authority, and forced into a new skin. Two sides of a continent that are utterly opposed, and yet part of the same organism, Europe, choked by the same crisis, with no option but to negotiate with one another.

Are all the styles of retreat in these two films a premonition of the dawning age of hibernation round the corner? Is there more to these blinkered scientists obsessed with the subject of their study (a planet, a skin) – subjects which will eventually come to bite them in the arse (like the economists that told us everything was ok)?

You could dismiss these queries as wild speculation, but essentially the horror which prompted the economic meltdown is of the same build as the primal dread lying at the heart of both these films: the alarm caused by a recognition of the gaping chasm between surface and depth. Just as the panic induced by a realization that subprime mortgages or government bonds were nowhere near as valuable in their substance as they appeared, both films contain the anxiety of an alarming disjuncture between the mask and what it conceals. In Melancholia, only Justine is able to see through to the depth of annihilation concealed by her sister’s trivial solicitudes; while in The Skin I Live In, Vera has to overcome the trauma of being locked in a skin which doesn’t correspond to her idea of herself; and Ledgard, locked in a world of surface, is incapable of seeing depth.

In both films, depth points to truth – the idea towards which one retreats. But for Von Trier, truth is pure metaphysical foreboding, a dismantling destructive force. For Almodóvar, truth is solace – that from which one draws comfort in times of suffering. In both pictures, surface is that attractive and misleading semblance of activity – one looks at it for pleasure or to see one’s own reflection, which anyway amounts to the same thing – the illusion of self-recognition. Real self-recognition involves digging; a reflective seeking for something buried; reading in the mysterious text of ourselves. Tellingly in Almodóvar’s film, end credits roll over the shape of the double helix glowing in the background – the ultimate sign of absolute distinction; the most mysterious text of all: DNA.

Does this opposition between the constricted apprehension of the North and the dilated sentimentality of the South, tell us what it means to be European at this point in history? Europe, home of the collapsing currency, blockages in the flow of international relations. Home of austerity and ashamed excuses ensuing from the blinkered profligacy of yesteryear. How does cinema, the kinetic art, deal with a well running dry? How does that omnipresent arbiter of flow, the screen, depict the putrefying currency, that other emblem of flow – the flow of power and production? If crisis is the blockage of flow, cinema is uniquely qualified to take from the energies which surround and determine a crisis, and channel them in a form which is abstract and visceral, (rather than literal or specific). These two bizarre, fascinating films offer us renewed proof of cinema’s embedded potential.